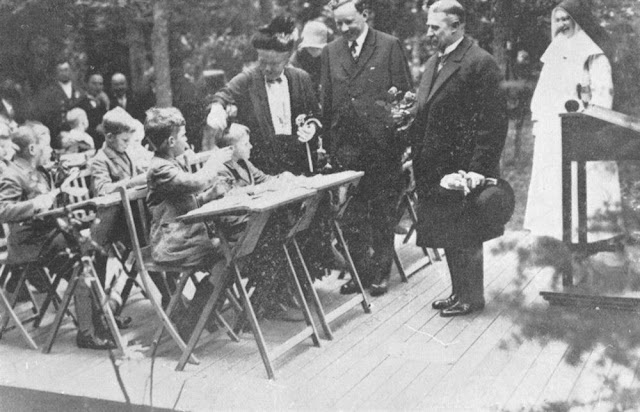

Open air schools were purpose-built educational institutions for children, that were designed to prevent and combat the widespread rise of tuberculosis that occurred in the period leading up to the Second World War. The schools were built to provide open-air therapy so that fresh air, good ventilation and exposure to the outside would improve the children's health. The schools were mostly built in areas away from city centers, sometimes in rural locations, to provide a space free from pollution and overcrowding. The creation and design of the schools paralleled that of the tuberculosis sanatoriums, in that hygiene and exposure to fresh air were paramount.

Open Air Schools were part of a larger open-air school movement which began in Europe with the creation of the Waldschule für kränkliche Kinder (translated: forest school for sickly children), in Charlottenburg, Germany, near Berlin, in 1904. Built by Walter Spickendorff and founded by the paediatrist Prof. Dr. Bernhard Bendix and Berlin’s schools inspector Hermann Neufert it offered “open-air therapy” to urban youths with pre-tuberculosis as part of an experiment conducted by the International Congresses of Hygiene. Classes were taught and fed in the surrounding forest. The movement quickly caught on throughout Europe and North America; construction of the buildings began in the first decade of the 20th century and carried on until the 1970s.

After World War I the movement became organized. The first International Congress took place in Paris in 1922, at the initiative of The League for Open Air Education created in France in 1906, and of its president, Gaston Lemonier. National committees were created. Jean Duperthuis, a close associate of Adolphe Ferrière (1879–1960), the well-known pedagogue and theorist of New Education, created the International Bureau of Open Air Schools to collect information on how these schools worked. Testimonies described an educational experience inspired by New Education, with much physical exercise, regular medical checkups, and a closely monitored diet, but there has been little formal study of the majority of these schools.

Later, the movement had an influence on the evolution of education, hygiene, and architecture. School buildings, for example, adopted the concept of classes open to the outdoors, as in Bale, Switzerland (1938–1939, architect Hermann Baur), Impington, England (1939, Walter Gropius and Maxwell Fry), and in Los Angeles (1935, Richard Neutra). This influence is the major contribution of the open-air schools movement, although the introduction of antibiotics, which increasingly provided a cure for tuberculosis, seemed to make them obsolete after World War II.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Open Air Schools were part of a larger open-air school movement which began in Europe with the creation of the Waldschule für kränkliche Kinder (translated: forest school for sickly children), in Charlottenburg, Germany, near Berlin, in 1904. Built by Walter Spickendorff and founded by the paediatrist Prof. Dr. Bernhard Bendix and Berlin’s schools inspector Hermann Neufert it offered “open-air therapy” to urban youths with pre-tuberculosis as part of an experiment conducted by the International Congresses of Hygiene. Classes were taught and fed in the surrounding forest. The movement quickly caught on throughout Europe and North America; construction of the buildings began in the first decade of the 20th century and carried on until the 1970s.

After World War I the movement became organized. The first International Congress took place in Paris in 1922, at the initiative of The League for Open Air Education created in France in 1906, and of its president, Gaston Lemonier. National committees were created. Jean Duperthuis, a close associate of Adolphe Ferrière (1879–1960), the well-known pedagogue and theorist of New Education, created the International Bureau of Open Air Schools to collect information on how these schools worked. Testimonies described an educational experience inspired by New Education, with much physical exercise, regular medical checkups, and a closely monitored diet, but there has been little formal study of the majority of these schools.

Later, the movement had an influence on the evolution of education, hygiene, and architecture. School buildings, for example, adopted the concept of classes open to the outdoors, as in Bale, Switzerland (1938–1939, architect Hermann Baur), Impington, England (1939, Walter Gropius and Maxwell Fry), and in Los Angeles (1935, Richard Neutra). This influence is the major contribution of the open-air schools movement, although the introduction of antibiotics, which increasingly provided a cure for tuberculosis, seemed to make them obsolete after World War II.

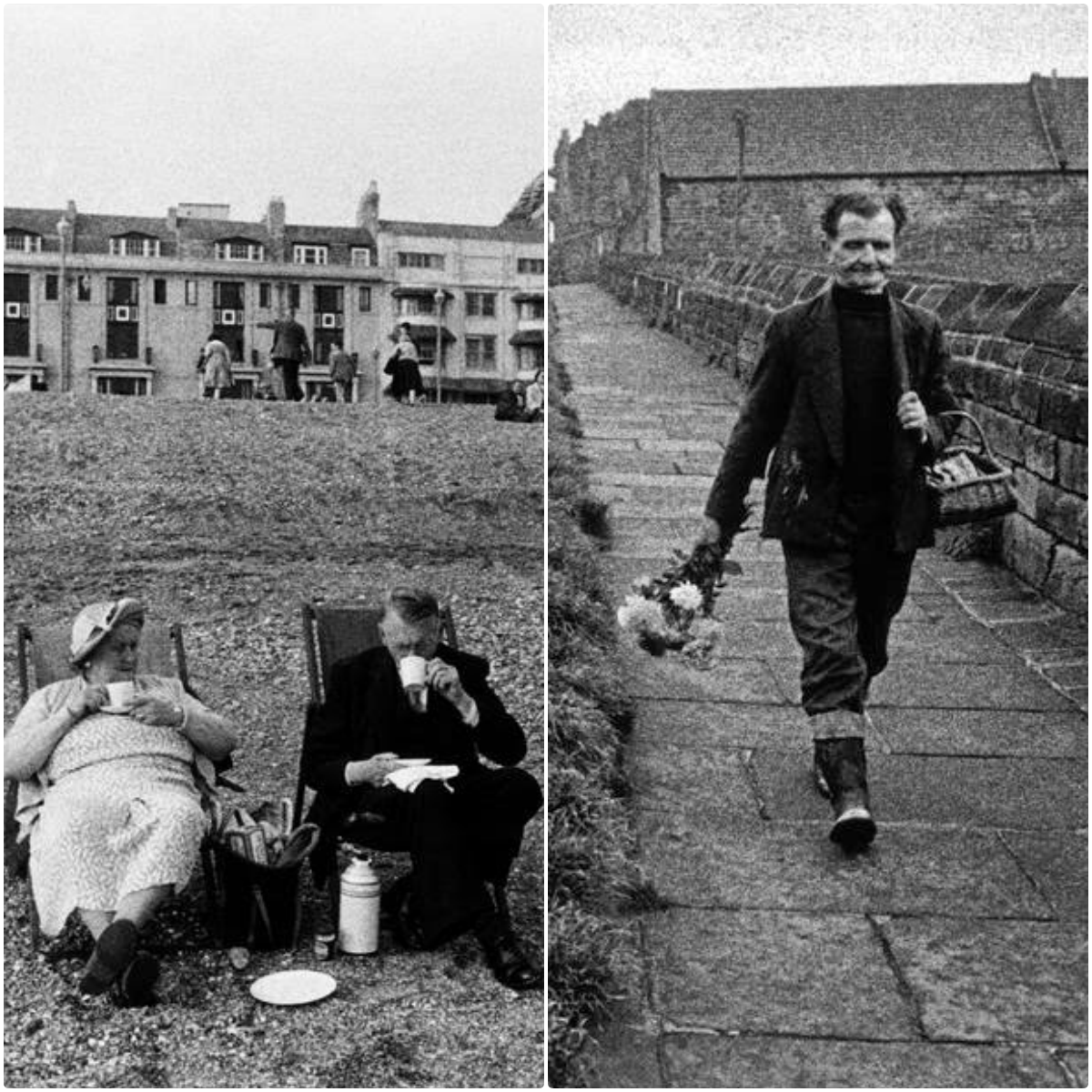

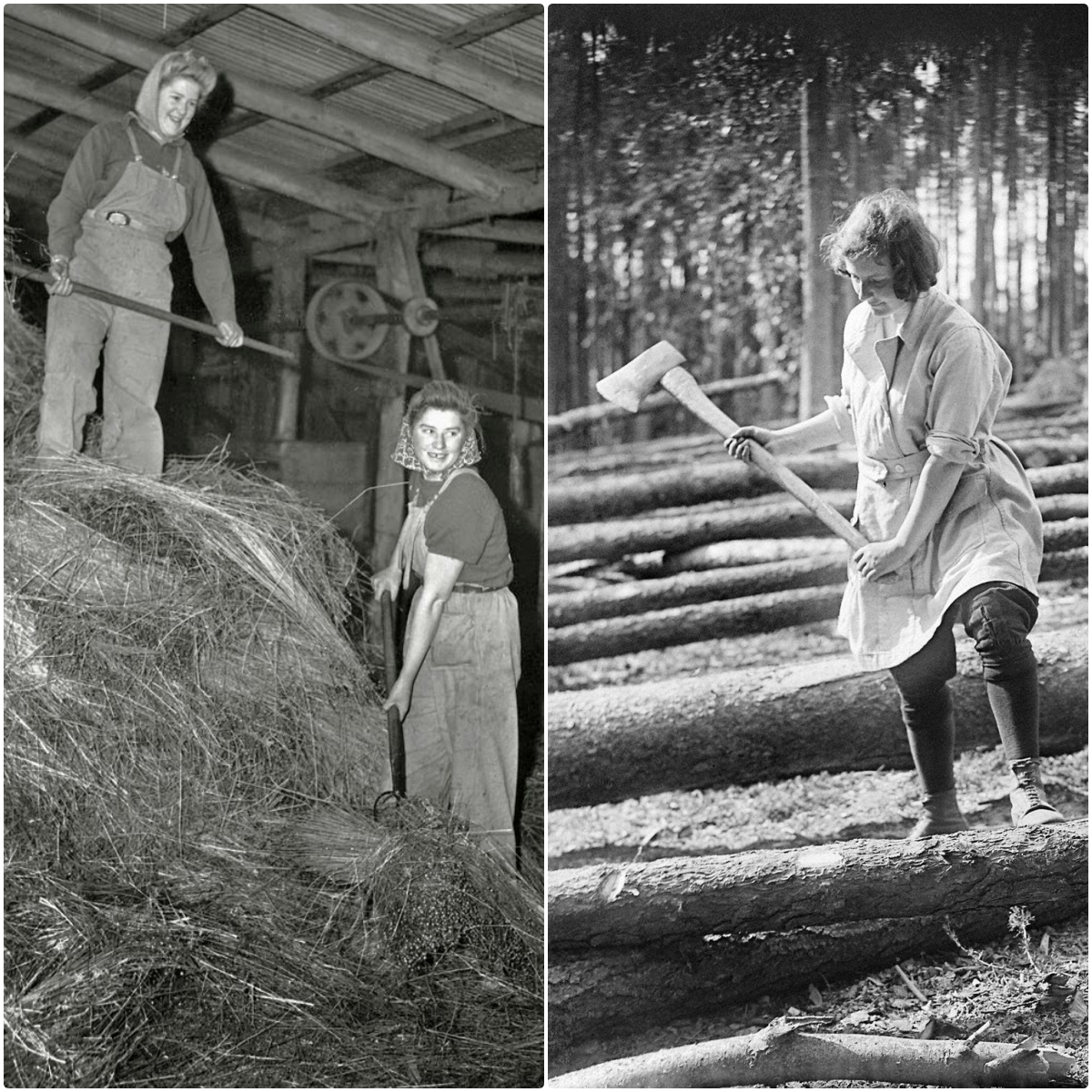

20 Amazing Vintage Photos of Open Air Schools in the Early 20th Century

20 Amazing Vintage Photos of Open Air Schools in the Early 20th Century

20 Amazing Vintage Photos of Open Air Schools in the Early 20th Century

20 Amazing Vintage Photos of Open Air Schools in the Early 20th Century

20 Amazing Vintage Photos of Open Air Schools in the Early 20th Century

20 Amazing Vintage Photos of Open Air Schools in the Early 20th Century

20 Amazing Vintage Photos of Open Air Schools in the Early 20th Century

20 Amazing Vintage Photos of Open Air Schools in the Early 20th Century

20 Amazing Vintage Photos of Open Air Schools in the Early 20th Century

20 Amazing Vintage Photos of Open Air Schools in the Early 20th Century

20 Amazing Vintage Photos of Open Air Schools in the Early 20th Century

20 Amazing Vintage Photos of Open Air Schools in the Early 20th Century

20 Amazing Vintage Photos of Open Air Schools in the Early 20th Century

20 Amazing Vintage Photos of Open Air Schools in the Early 20th Century

20 Amazing Vintage Photos of Open Air Schools in the Early 20th Century

20 Amazing Vintage Photos of Open Air Schools in the Early 20th Century

20 Amazing Vintage Photos of Open Air Schools in the Early 20th Century

20 Amazing Vintage Photos of Open Air Schools in the Early 20th Century

20 Amazing Vintage Photos of Open Air Schools in the Early 20th Century